The Desire to Win

Aligning Innovation with Corporate Priorities

If You Only Have a Minute

Many corporates still struggle to drive effective innovation, largely because they don’t answer three key questions — do we have the Right to Win, the Desire to Win, and the Path to Win? In this article, we focus on that second question:

Wanting to innovate isn’t enough, your organization must have a Desire to Win — This means innovation should be a core part of a company’s business strategy and embedded in success metrics

Building and maintaining a desire to win requires managing four key areas — Strategic alignment between the business and innovation initiatives, relevant metrics that focus on impact not vanity, formal & informal governance that accelerates innovation rather than hamper it, and optionality that provides multiple paths forward

The Wright Partners approach starts building the Desire to Win even before we secure a mandate — we leverage a lightweight, outcomes-driven model that addresses each of the four areas of alignment

Corporate innovation is incredibly difficult to get right. In fact, 94% of global executives are “dissatisfied with their organization’s innovation performance,” according to McKinsey research. This gap between intention and outcome is driven, in large part, by a failure to answer the three key questions of innovation — do we have the Right to Win, a Desire to Win, and a Path to Win?

This is the second in a three-part series, written as part of EDB’s Corporate Venture Launchpad programme, designed to enable companies to launch a new venture from Singapore. In our previous post, “The Right to Win — Leveraging Corporate Assets for Disruptive Innovation,” we focused on how to identify and leverage true unfair advantages when creating new products, business models, and ventures. In today’s discussion, we dive into how to ensure that innovation maintains the support of the organization.

The Second Question of Corporate Innovation

With 75% of corporates saying that “innovation” is one of their top priorities, it would be easy to think that a Desire to Win already existed. Delivering successful innovation that has real impact, however, is much more complex. It involves ongoing management of four key areas:

Strategic Alignment — Is there a clear strategy for the role innovation plays in the company’s overall growth strategy? Is it tackling problems that are relevant to the business? Is this alignment being reviewed and updated regularly?

Relevant Metrics — What metrics are being used to measure progress? Are they impact-focused or vanity metrics? Do they give insight into the effectiveness of the innovation process?

Formal & Informal Governance — Who are the key innovation champions within leadership? Are there communication and governance structures supporting innovation? How are other parts of the organization connecting with innovation teams?

Nurturing Optionality — What is the strategic approach to building a new innovation? Is it embedded in a business unit or independent? Is this strategy dynamic or static (for instance, can an independent venture be spun into the business)? How does the innovation get the right resources and priority when it still has minimal impact on the business or when it needs to pivot?

Developing each of these areas is critical for ensuring that innovation initiatives, whether they are close to the core or pushing the boundaries with new markets and business models, deliver results and maintain the support of the organization.

1. Corporate Priorities Are Your Priorities

One of the biggest challenges corporates face is ensuring that their innovation initiatives deliver real value to the organization. In a study of over 12 years of data, Strategy& found that R&D spending had no significant correlation with sustained financial performance. This means that how a company is spending those dollars is far more important than how much they spend. In fact, the more a company spends the more important and more difficult it becomes to manage. Although over half of corporate leaders struggle to bridge the gap between innovation strategy and corporate strategy, when you look at those that invest the most (15% or more of their revenue), the number who are struggling jumps to 65%. Innovation leaders clearly need to spend time finding that alignment early on and maintaining it over time.

The first and most important step is to understand what the strategic goals of the company currently are, how they want to achieve those, and what role innovation can play. At the strategic level is the company looking to aggressively grow into new markets and segments, focusing on dominating existing markets, or potentially consolidating and streamlining the organization? This helps to prioritize the type of innovations that a company is pursuing, whether they are process innovations or new products. Also, what are the key market trends the company is focused on as opportunities or challenges? This helps prioritize the areas for experimentation and reduces the tendency to chase shiny new technologies or trends.

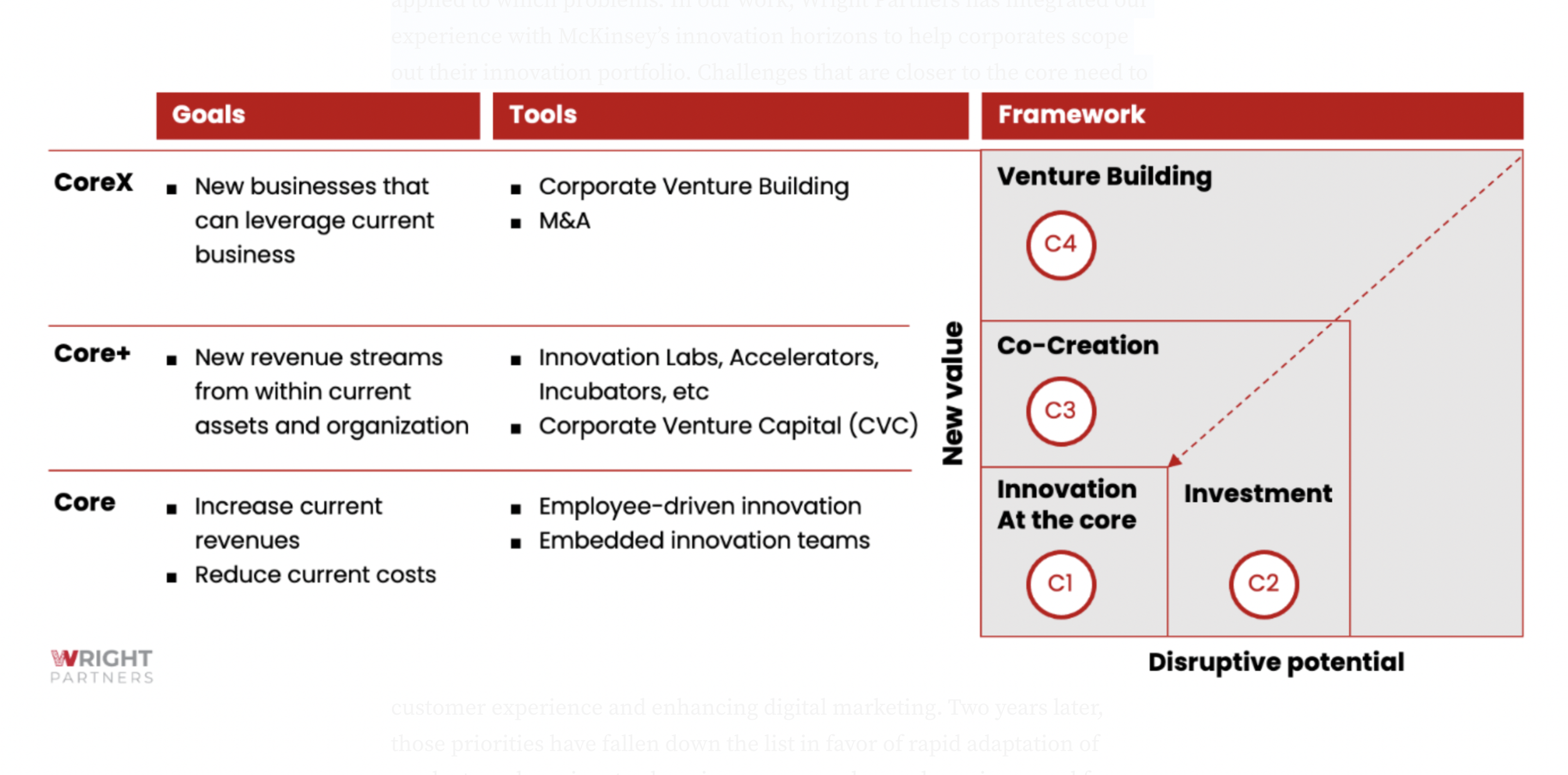

The second step is understanding which innovation tools are going to be applied to which problems. In our work, Wright Partners has integrated our experience with McKinsey’s innovation horizons to help corporates scope out their innovation portfolio. Challenges that are closer to the core need to be more targeted and carefully managed to prevent business disruption or customer confusion. These are best tackled by incentivizing existing teams to spend time innovating or embedding small innovation teams that work hand-in-hand with the business unit. For corporate challenges that are farther away from the core (Horizon 2 and 3), such as moving into adjacent markets and segments or disrupting existing business models, leveraging other tools like Open Innovation platforms, CVCs and Corporate Venture Builders will be more effective.

The third and final step is to ensure alignment and regular re-alignment of innovation initiatives with strategic and business-level priorities. Even if the high-level innovation strategy is well defined and communicated, individual initiatives need to ensure that they are clearly aligned with specific priorities and that those priorities haven’t changed. The Covid-19 Pandemic is a clear, if extreme, example of how priorities in an organization can change rapidly. Pre-pandemic, corporate growth plans were focused on building consistent customer experience and enhancing digital marketing. Two years later, those priorities have fallen down the list in favor of rapid adaptation of products and services to changing consumer demands, an increased focus on partnerships to improve business resilience, and a strong emphasis on employees and talent management. Innovation leaders need to be in the loop as these priorities shift, adapt their portfolios, and jettison projects that won’t deliver value against these new goals.

2. Metrics Are About Impact, Not Vanity

In building and maintaining support for innovation initiatives, it is critical to demonstrate impact in a concrete way. Yet many innovation teams get caught up in “innovation theatre,” emphasizing how many workshops they ran, ideas they generated, or customers they interviewed. However, these stats don’t give corporate leaders insight into the value of those activities. Rather than vanity metrics, innovation teams need to be focused on impact. Metrics for impact need to be (1) relevant for different types of innovations and (2) applied to both individual ideas and entire processes.

Relevant Metrics

Choosing the appropriate, impact-driven metrics will depend on the techniques being used and where on the innovation horizon it falls. It is generally easier to quantify the impact of innovations closer to the core. Existing demand curves and cost structures are well-known and a solution that changes processes or improves sales will have a very clear value to the business. Farther out on the horizon, new ideas will be harder to quantify. These types of innovations require different metrics for each stage of development that highlight the potential for impact.

Properly incorporating tailored metrics into a stage-gated process will give business leaders useful, actionable insights into ongoing initiatives. These tailored metrics should match the stage of development and avoid traditional business measures like profitability and ROI that may actually restrict or hamper experimentation. They should also focus on early signs that the solution adds value to the customer or the company. For instance, in early ideation, rather than the number of customers interviewed, leaders should evaluate quickly what is the value of the pain points to be solved through actual engagements with them. At Wright Partners, we make our early metrics actionable by getting Proofs of Concept into the hands of customers and even running live pilots within the first 10 weeks of a venture.

Measuring Processes

Beyond measuring the progress of your individual initiatives, it is also important to have metrics in place to judge the effectiveness of your innovation processes. High-level metrics like sales from new products versus innovation investment can give a general sense of how effective your innovation strategy is but more granularity is required if innovation leaders want to maintain the support and buy-in of their organizations. The focus here should be on speed and quality using milestones that are relevant to the type of innovation. For instance, average time to implementation for process innovation versus average time to revenue for new ventures. These milestones should also capture how well a process handles failure by measuring things like average time to kill failed products. If struggling solutions are allowed to drag on for months or even years before being killed, then the innovation process is wasting time, money, and resources that could be better spent. At Wright Partners, we approach corporate venturing like an independent start-up would, seeking to attract outside investors, who are more objective and less vested in the venture, as validation of the business model and approach.

3. Governance Keeps You Relevant

Getting strategic alignment and agreeing on relevant metrics creates the groundwork for launching innovative initiatives and demonstrating value, however, using that framework to earn and maintain support from key leaders is what ultimately drives successful innovation. This trust can initially be built informally by developing internal champions and networks but, ultimately, needs to be formalized into lightweight but effective governance.

Champions & Connectors

Innovation champions play a pivotal role in driving the adoption of new processes and approaches. The right champion builds coalitions, obtains access to resources, and, most importantly, develops buy-in from other executives. 70% of organizational change efforts fail, in large part due to a lack of buy-in, hence, cultivating champions for new innovation approaches and initiatives is critical for success. At Wright Partners, we cultivate sponsors within our corporate partners for each of our ventures and then bring them into a more formal governance structure.

Developing a network of connectors is also important. These connectors help innovation teams gain access to key resources, offer insights and context from the broader organization, and provide updates on changing priorities. The ability to access resources is particularly important when it comes to leveraging corporate assets to create an unfair advantage, as we discussed in the previous article. However, access to other resources like legal, compliance, HR, and procurement is also important in helping overcome obstacles and accelerate innovation.

Formal Governance

Converting these informal support networks into formal governance is crucial for long-term success but should be done carefully and only as needed. Placing too much bureaucracy and reporting onto innovation processes can hamper or even kill them. At Wright Partners, we advise our clients not to create huge innovation programs, which often require substantial time and money upfront, before any innovation has started and long before the corporate knows if it’s the right process for them. Instead, we emphasize creating small groups of empowered executives to make decisions and manage risks, scaling up the number of innovation initiatives over time.

When formal governance is implemented, it should focus on managing risk while promoting speed and learning. Innovation champions or sponsors should meet regularly with their teams, review milestones, and be empowered to access resources and provide support. A more formal committee of executives can then be tasked with making major investment decisions, managing risk appetite, and reviewing the alignment of strategic priorities.

Wright Partners is currently working with a global bank where our venture presents to a formal investment committee twice a year to report on milestones, request the next 6 months of funding, and propose the next set of milestones and funding requirements. This ensures continuous alignment on priorities, goals, and potential risks while giving the venture the ability to propose relevant milestones and space to freely drive the business in the intervening months.

4. Nurturing Optionality Gives Flexibility

Having the right governance structures and metrics in place will help ensure the relevance of a company’s innovation portfolio, but to be able to drive successful outcomes, especially farther out on the innovation horizon, a company has to maintain flexibility in its approach in order to create what Wright Partners calls “optionality.”

Venture Hypotheses not Corporate Strategies

Corporates can no longer afford to spend months (and often millions of dollars on consultants) to create static, long-term Corporate Strategies. Even before the pandemic, the value of a 5-year strategy was being questioned and today there is more pressure than ever to build dynamic plans that can address high market uncertainty. This means that companies have to remain flexible in how they support and grow innovations. They have to allow a certain level of freedom when setting goals for outside-the-box innovations, especially new ventures. In turn, these ventures need to stay focused on proving a hypothesis for market demand rather than chasing ever-changing corporate strategies. This approach can create short-term gaps between a venture’s goals and the company’s strategy but, by maintaining optionality, the company can support the new venture in a way that adds the most value.

Venture Hypotheses not Corporate Strategies

Corporates can no longer afford to spend months (and often millions of dollars on consultants) to create static, long-term Corporate Strategies. Even before the pandemic, the value of a 5-year strategy was being questioned and today there is more pressure than ever to build dynamic plans that can address high market uncertainty. This means that companies have to remain flexible in how they support and grow innovations. They have to allow a certain level of freedom when setting goals for outside-the-box innovations, especially new ventures. In turn, these ventures need to stay focused on proving a hypothesis for market demand rather than chasing ever-changing corporate strategies. This approach can create short-term gaps between a venture’s goals and the company’s strategy but, by maintaining optionality, the company can support the new venture in a way that adds the most value.

Which Way to Spin

Given the dynamic nature of corporate strategy and the speed at which ventures have to adapt, companies need to create space where these ventures can grow and demonstrate whether they can drive internal value or are best placed as external endeavors. In our experience, this means creating as much space as possible for a spin out and avoiding the premature assumption that they can be spun in as a new business unit. This bias towards spin out is driven by a few key observations:

Over-Valuation — Internal ventures are often given ample space to play, which can give them extra time to find market fit, but can also result in over-investment by the corporate. In these cases, a company can often over-value the money and time spent on exploration creating an inflated valuation when they decide to seek external funding. Meanwhile, external investors look only at the traction achieved and may be unwilling to match these excessive valuations.

Lack of Founder Incentives — Innovations are most successful when everyone’s incentives are aligned. For ventures, this means giving the founding team a meaningful stake in the business (something that external investors look for). However, if a company has already over-invested in an idea, “giving” an equity stake to the founders as part of a spin-out can appear like a substantial loss in value.

Political Risk — If a venture has been supported as a potential new business unit, it is much harder to spin it out. Most likely, there has been substantial political capital spent to frame the innovation as a “strategic investment.” As a result, the venture coasts along as a “zombie venture” that is never given the space to scale or die like most new businesses.

Always Spin Out?

No! However, at Wright Partners, we believe in building corporate ventures with the intention that they will be spun out. We find that this gives the venture the right pressure, tension, and momentum while providing optionality to the corporate to spin in the venture once it is ready. The reasons are very simple and anchored in the basics of corporate finance, which we have explored in earlier articles. Money today is better than money tomorrow, hence limiting the corporate’s spend early, and potentially taking over the venture later is a more efficient use of cash. In addition, this optionality ensures that the venture either aligns with the corporate strategy over time OR remains as an outside venture supporting the corporate (which we often see as a relevant option).

Desire to Win in Corporate Venture Building

The Desire to Win is critical for any innovation endeavor. However, for initiatives farther out on the innovation horizons, it is even more important and more difficult to build and maintain that desire. As a result, Wright Partners has embedded the principles discussed above in every step of our process:

Strategic Alignment — Given that Venture Building is focused on areas of high uncertainty, we spend a substantial amount of time before finalizing a mandate to understand how venturing fits with a partner’s overall strategy and risk appetite. We have developed a Venture Building Assessment for corporates to help them understand the key elements required for success. We also align on how an independent venture will be structured, ensuring they have the optionality to spin in or even stop the venture.

Relevant Metrics — Our design and build phases are built on 2-week sprints with concrete milestones and deliverables at the end of each sprint. These milestones are tailored to the stage of the venture and focused on demonstrating the potential for the solution and how it will deliver value.

Formal & Informal Governance — We identify key sponsors and agree on governance structures and timelines as part of our early conversations with corporate partners, often before we have even formally won the mandate. In keeping with our philosophy on lightweight and outcome-focused governance, we generally recommend a Venture Board that is driven by our sponsor and meets with the team every two weeks to ensure rapid progress and continuous alignment. We also support the creation of a more formal Investment Committee that is composed of executives with the ability to make major investment and risk decisions but only meets every few months to review major milestones.

Optionality — This is one of our core values, as we believe that creating optionality for corporations allows them to build better while maintaining choice and limiting expenditure. This ensures that the decision on spin out (take external investment) or spin in (pay off the founding team for success) happens when the strategy of the corporate and traction of the venture align and not before.

Ultimately, the Wright Partners model is focused on managing risks while giving the venture the freedom to move and learn quickly. You can learn more about our approach to governance in a previous article, “The Basics of Corporate Governance for Venture Building.”

We are also pleased to be an appointed venture studio of EDB’s Corporate Venture Launchpad 2.0. CVL 2.0 is an expanded S$20m programme by EDB New Ventures, designed to enable companies to incubate and launch a new venture from Singapore, supported by venture studios experienced in corporate venture building. You can also find out more on our website.

Interested to learn more about investable ventures? Drop us a line: contact@wright.partners.

Authors:

Stefan Jacob, Venture Partner at Wright Partners

Ziv Ragowsky, Founding Partner at Wright Partners

Liked this article? Explore the other articles of this three-part series here: