The Basics of Corporate Governance for Venture Building

source: Unsplash

If You Only Have a Minute

Finding the right balance of managing risk while expecting failure/ pivots/ changes is key in maximizing success of corporate ventures. As a corporate, you should:

Set clear limits on ventures, but do not be prescriptive about the process - Make it such that regardless of process, risk is comfortable because the right limits are set in place.

Think like a shareholder, not an executive — Protect your interests through board/shareholder reserved matters. The focus is learning and anything that supports learning should be provisioned for the founders up to the limits mentioned above.

Hold optionality — Retain the rights to the financial and strategic returns, but responsibilize the founders to execute by giving them the tools and sharing the rewards.

In this article, we hope to highlight some of the key challenges that corporate innovators face in formulating the right governance for their disruptive ventures. We propose a practical way forward, where instead of solely relying on corporate policy, the corporate should focus on using all the levers it has to manage the risks that these innovative activities pose. These include limiting initial investment, creating clear separation between the venture and the corporate, and creating accountability for results instead of process adherence, among others.

Most discussions between innovators and the guardians of corporate policy descend quickly into mudslinging. On the one hand, innovators complain that corporate policy-makers are dinosaurs who do not understand the fast-paced modern world of technology. Policies thus end up being too antiquated, onerous, and inflexible. On the other hand, corporate governance folks accuse the innovators of being entitled brats. These “innovators”, they complain, bring in no money and are completely dependent on corporate funding, yet seek to skirt the corporate rules that apply to everyone else so they can buy expensive computers, hire indiscriminately, and spend money on shiny new projects that do not benefit business outcomes.

To have a productive conversation, it is important for founders to recognize that corporate governance in an existing enterprise is nothing but formalized institutional memory on what has previously helped a business succeed, what mistakes were made, and what risks could prove catastrophic. Every enterprise was once a startup, and these guidelines were slowly developed as that startup discovered and refined its business model.

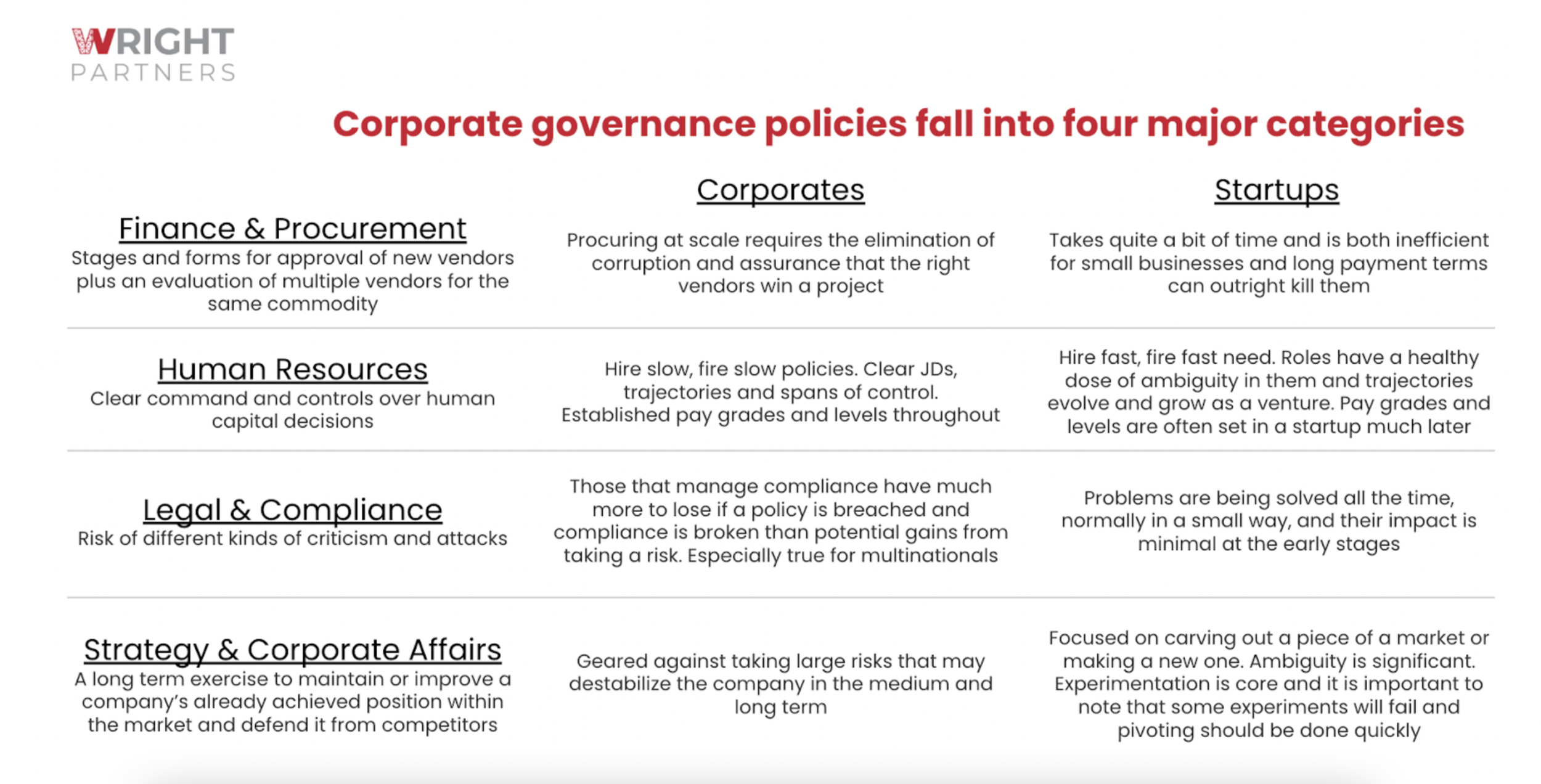

Broadly categorized, corporate governance falls into four main buckets, namely, Finance & Procurement, Human Resources, Legal & Compliance and Strategy & Corporate Affairs. Look into any corporate organization structure and you’ll find commonalities in these areas. Below you can find examples of such policies, and the rationale for them.

It is, however, key to understand that many (though not all) corporate governance policies were developed to address the specific circumstance of a company. A multinational bank will have very different know-your-customer policies from a multinational mining company; in turn, a multinational real-estate company will have very different procurement policies from a startup developer starting its first 20-unit project. Which brings us to the innovation dilemma — the innovator is tasked to pursue a new business model, but yet is faced with the incumbent governance built for a completely different one.

So then, what is the type of governance that will be needed for the investable venture that can be built by the corporate and what should it focus on?

Speed — At a new venture where a business model is yet to be uncovered, the manpower cost of executives typically far outweighs the business risk of most decisions. The biggest cost therefore to a startup is indecision.

Learning — When a corporate pursues a new venture, they are necessarily entering an area they have little to no experience in. The governance must promote learning, not failure avoidance, as it is yet unclear which actions will lead to failure and which to success. In reality, this means that corporate venture teams and their leaders will have to be okay operating in uncertainty and experiencing failure. No startup succeeds without this.

Managing risk — To venture means “to dare or go somewhere that may be dangerous or unpleasant.” Empowering risk-taking is important, and counterintuitively, corporates can promote this by managing the potential consequences of those decisions rather than scrutinizing the decision itself.

Innovator Alignment — These are the men and women in the arena. While it is key for corporates to ensure governance matches their needs, it is equally important to ensure founders understand that the governance is there to aid success instead of imposing overbearing requirements.

In summary, the ability to manage risk while interacting with uncertainty through curiosity are a strong base on which to build governance infrastructure. This will both help the corporate and the venture founder maximize the chances of success.

Here are some guidelines and rules of thumb we have found useful:

Set clear limits on your ventures, but do not be prescriptive about the process - make it such that regardless of process, you are comfortable with the risk because you have the right limits set in place.

Capital limit to ensure operations over a set period of time without the need to come for constant new approvals (hurting speed), focusing on agreement as to how much time is needed to achieve learning results.

Spending limits that ensure the ability to execute experiments quickly while managing them as experiments (limiting risk) scaling them up with a governance decision as founders align on the right path forward.

2. Think like a shareholder, not an executive — Protect your interests through board/shareholder reserved matters.

As mentioned, the focus is learning and thus anything that supports learning should be provisioned for the founders up to the limits set above.

Venture Capital companies have clear elements of governance within their deal documents that manage their reserved matters while aligning founder interests. Corporates can learn from both VCs and their own CVCs when setting up their venture building capabilities.

Limit the founders’ ability to make potentially catastrophic decisions (e.g. entering exclusive intellectual property transactions) while giving them free reign on decisions that will not make any material difference on shareholder value (e.g. choosing cloud service providers without a formal procurement exercise)

3. Optionality — retain the rights to the financial and strategic returns, but responsibilize the founders to execute by giving them the tools and sharing the rewards.

This is especially important as a startup moves fast while taking time to establish its core place within a market while, on the other hand, a corporate can make a well-researched strategy decision while changing it a few months later as the strategy proves not to achieve its goals. This could mean that the decision, for example, to own a venture wholly or partially depends on the latest strategy and not when the initial effort was initiated.

Hence, to achieve the goals of the corporate, deciding early whether to keep the venture as a new business unit or a less than majority owned business is always done with lack of information. Optionality, as mentioned above, helps tackle this “future telling” problem.

As such, having founders who are incentivized and aligned to do what is best for the venture while the corporate keeps the ability to see it grow under control while refining its own umbrella strategy is a winning governance move.

Ultimately, our model helps corporates put together the right governance to manage risk while ensuring the venture’s long term success. In a future article, we’ll dive more specifically into how corporates and founders can build governance structures through clauses, rights, and decision-making.

Authors:

Toi Ngee Tan, Founding Partner at Wright Partners

Ziv Ragowsky, Founding Partner at Wright Partners

Ajay Taunk, Senior Venture Architect at Wright Partners